Is stress something that happens to us or is stress the result of our interpretations and reactions to events?

Schwarzer and Taubert (2002) proposed a cognitive-transactional theory of stress that recognizes the reciprocal and continuous interaction between us and our environment. In this framework, stress is how we appraise and interpret environmental events that we perceive will tax our resources or threaten our well-being. The resulting proactive-coping framework can shift our perspective of events as stressors that make us sick to recognizing events as opportunities for growth. The event doesn't cause us stress, our inability to handle the event is what breaks us down. A proactive coping perspective helps us prepare for and leverage stressful events for adaptability, performance, growth, resilience, and wellness.

Let's explore the Schwarzer and Taubert cognitive-transactional theory to discover functional coping strategies for building resilience, mindset, and skills for facing and conquering stressful events as opportunities for growth.

Emotion to cognition

Lazarus (1991) presented a process of emotion that consists of antecedents, mediating processes, and effects. Antecedents include personal resources and objective demand, as follows:

- Personal resources are factors such as wealth, relationships, skills, values, and beliefs.

- Objective demands include critical events and situational constraints.

- Mediating processes are the cognitive appraisals of resources and demands related to coping efforts.

Building on the Lazarus’ cognitive-transactional theory of stress framework, Schwarzer and Taubert (2002) proposed a proactive coping theory. The theory provides functional strategies that use goal-oriented and long-term behaviors that allow people to anticipate and handle perceptions of stressors positively before the stressors are even faced. A key to functional coping strategy is to shift focus from “mere responses to negative events toward a broader range of risk and goal management that includes the active creation of opportunities and the positive experience of stress” (p. 10). In other words, an essential strategy for handling a challenge is to recognize it as a growth opportunity. Reacting causes sickness, proacting nurtures wellness.

Stress is subjective

Schwarzer and Taubert (2002) emphasized that stressors exist mostly in the individual's interpretation. The event itself does not cause stress. The individual's reading of and inability to handle the event cause stress. Goals and expectations may create opportunities and risks. Striving for rewards, goals, and benefits can generate unanticipated stress when we perceive events as threats.

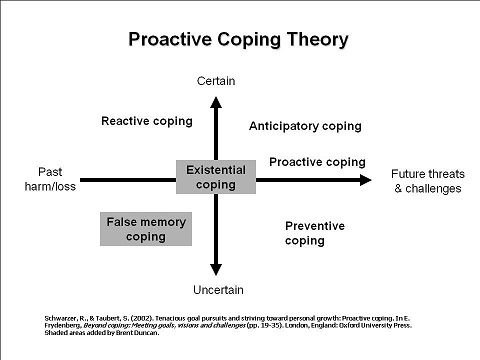

Schwarzer and Taubert (2002) observed that stress can reflect past and future encounters and that these encounters can be either certain or uncertain. An individual may suffer from distressing events earlier in life, may struggle with current events, and may fear future events. Mourning the past, fearing the present, and dreading the future do not generally combine as a functional coping strategy.

Coping strategies

Due to the complexity of stress, especially in social contexts, coping cannot be understood by merely understanding and managing fight-and-flight and rest-and-relax modes. Functional coping depends on context, perspective, pre-action, and reaction. “One can cope before a stressful event takes place, while it is happening, or afterward” (Schwarzer and Taubert, 2002, p. 7). This illuminates four coping strategies that exist on planes between past harm and future threats, and certain or uncertain: reactive, anticipatory, preventive, and proactive [Image: Proactive Coping Theory].

Reactive coping

Reactive coping refers to how people deal with harm from past and present experiences, like a divorce, criticism from a boss, or getting fired. The individual develops strategies for compensating for loss or alleviating harm. Dysfunctional methods of reactive coping include holding grudges, wallowing in misery long after the event passes, and allowing the event to falsely taint perceptions of current and future experiences. The functional way people reactively cope is by finding meaning in the experience, recognizing benefits, and adjusting goals and life perspectives that will help them to develop resilience.

Anticipatory coping

Anticipatory coping refers to dealing with imminent events that may be threatening or challenging, like a test or a job interview. Anticipatory coping strategies can include engaging in problem-solving, increasing effort, enlisting help, and investing resources. A key to successful anticipatory coping is developing self-efficacy in coping, the optimistic belief that the individual can meet and beat the challenge.

Preventive coping

Preventive coping is a risk management strategy that allows individuals to prepare for critical events that may or may not occur in the distant future like getting fired, robbed, injured, hit by a natural disaster, killed by a disease, attacked by terrorists. Since it is dealing with ambiguous uncertainties, preventive coping involves a spectrum of coping behaviors designed to minimize the severity of future events by strengthening resilience. For example, saving money, buying insurance, getting out of debt, strengthening relationships, getting another degree, diversifying skills, stocking guns and food supply, learning first aid, wearing masks, isolating self from society, making plans “just in case.”

Although some can experience anxiety about future uncertain events, preventive coping is generally sparked more by worry than by anxiety. Coping self-efficacy serves as a prerequisite to planning and carrying out the strategies that can strengthen resilience against future uncertainties.

A negative aspect of preventive coping is that fear of future and imaginary events can inhibit an individual's capacity to enjoy life now. The individual can live in a perpetual duck-and-cover mode, fearing something that may never occur; resenting and even attacking others who fail to fear imagined events as they do.

Proactive coping

Proactive coping is a goal management strategy that provides an individual with the perception that future risks and threats are demanding situations that provide opportunities for personal growth. Proactive coping provides positive steps toward a constructive path for life improvement that builds resources that ensure progress toward and quality of performance.

Proactive coping facilitates better conditions and higher performance levels that foster a more meaningful and purposeful life. Proactive coping allows the individual to tap the productive arousal and vital energy of stress rather than react passively to life events.

Limitations

Although proactive coping theory provides a building block for developing a functional strategy for preparing for and facing challenges for growth, it is missing some potentially important coping strategies for modern life. Most glaring is a category for existential coping, how people interpret and cope with immediate events that can be certain, imagined, or distorted. Similarly, the theory does not seem to consider a category for false-memory coping, how people cope with imagined or distorted past events. A possible third category is proxy-coping, how people cope with events that are faced by others but not experienced by the individual. Events that are imagined or experienced in proxy may seem just as real or even worse to the individual learning about a remote event than it is for the people facing the actual event. Recognizing the limitations of subjective memory and interpretation might help facilitate functional coping strategies more grounded in reality.

References

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. London: Oxford University Press.

Schwarzer, R., & Taubert, S. (2002). Tenacious goal pursuits and striving toward personal growth: Proactive coping. In E. Frydenberg, Beyond coping: Meeting goals, visions and challenges (pp. 19-35). London, England: Oxford University Press. Retrieved Schwarzer, R., & Taubert, S. (2002). . In E. Frydenberg (Ed.),” Beyond coping: Meeting goals, visions and challenges (pp. 19-35). London: Oxford University Press.