Understanding the communications cycle

Sender and encoding

Communication starts with a sender and a receiver in a context. The sender formulates ideas into a message intended to draw out a response from the receiver; this is “encoding,” meaning to develop a message in a format the receiver can recognize and understand. To properly encode a message, the sender might consider the language, background, and culture of the individual receiving the message. Other variables the sender might consider while encoding include the events, the environment, and the method. Methods include written, verbal, and nonverbal communication.

It’s not what you say but how you say it

At this stage, it becomes essential to understand the role nonverbal communication plays in creating shared meaning. Nonverbal communication is “transmitting messages through means other than words” (DuBrin, 2000, p. 294). Nonverbal communication conveys the feeling behind a message through posture, facial expressions, appearance, vocal inflections, the distance between the communicators, and the environment.

Research consistently shows that at least half of all meaning in a message is nonverbal (DuBrin, 2000). Still, nonverbal communication can carry the entire message. For example, if a boy says to a girl, “I like you,” while he smiles, the nonverbal message strengthens the verbal message. However, if the boy scowls while saying, “I like you,” the scowl may overwhelm the meaning of the words, causing the girl to understand that the boy does not like her.

This example helps to dramatize the critical role nonverbal communication plays in helping to establish and maintain relationships. Communication is not only what a person says but also how they say it. Sometimes, how a person says something is all that matters.

We should also be careful about misreading non-verbal communication, especially with people from other cultures. For example, in American culture, smiling and nodding communicates agreement. However, in Japanese culture, nodding and smiling can mean that the individual does not agree or understand but is being polite so as not to cause embarrassment to others (DuBrin, 2000). This cultural characteristic can lead to misunderstanding and conflict if the American interprets smiling and nodding as agreement.

Media channel

The sender transmits the encoded message through a media channel to the receiver. Common media channels include face-to-face, telephone, letter, email, and the Internet. The channel directly affects the quality of communication.

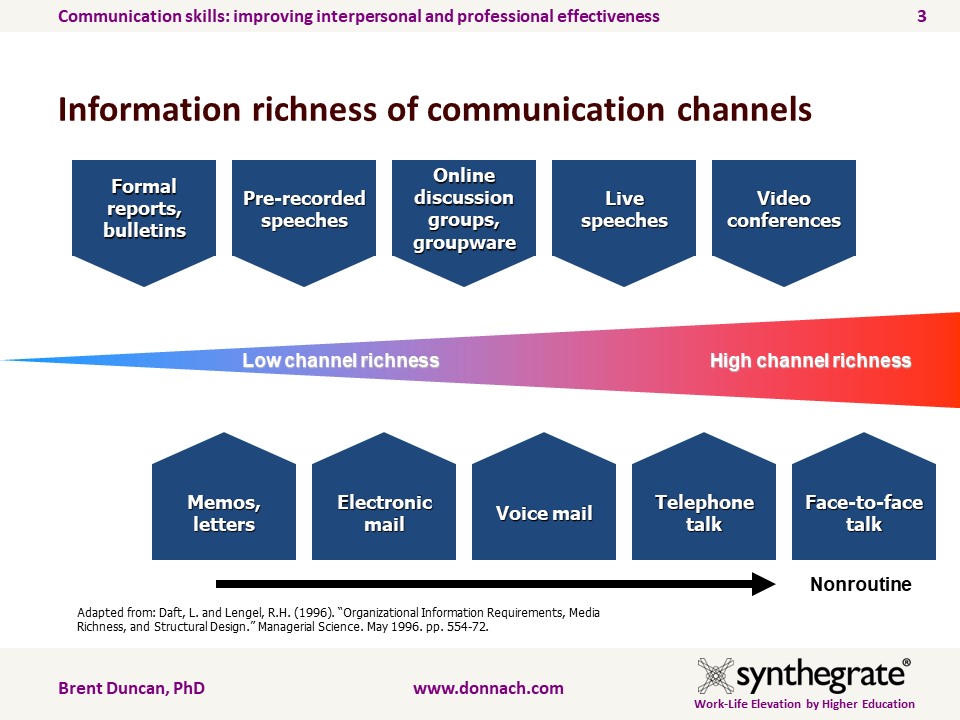

Researchers Richard Daft and Robert Lengel (1996) found that channels differ in their capacity to convey information. In other words, some channels are more effective than others [See Image 2]. Daft and Lengel found that some channels are “rich” in that they can support multiple cues simultaneously, facilitate rapid feedback, and are very personal. Their research identified the face-to-face channel as the richest because it provides the maximum amount of information to be transmitted during a communication event. In other words, face-to-face communication provides multiple information cues (words, postures, facial expressions, gestures, intonations), immediate feedback (verbal and non-verbal), and personal touch.

On the other end of the scale, Daft and Lengel (1996) found that impersonal communication channels to be the least rich. Impersonal communication channels include reports, memos, and emails. The critical message from Daft and Lengel’s model is that choosing the right media channel, or a combination of channels, can enhance communication effectiveness.

Image 2: Information richness of communication channels

Image 2: Information richness of communication channels

Receiver and decoding

The receiver is the person to whom the sender sends a message. The receiver reconstructs the message into something resembling the sender’s original idea, a decoding process.

Noise

The information sent is not necessarily the information received. Different words and symbols can mean different things to different people, especially people from diverse cultures. Communication usually takes place in environments that contain distractions to successful communication. These distractions are “noise” barriers to successful communication (Schermerhorn, Hunt, & Osborn, 2007). Noise can take the form of physical and psychological distractions.

Physical barriers. Common sources of physical noise include other conversations, ringing telephones, blasting music, traffic, crying children—anything that distracts from clear transmission and reception of messages. Physical communication barriers can be reduced by eliminating them or modifying or changing the environment. Non-verbal and environmental elements can also contribute to noise.

For example, the layout of an office, hand gestures, and vocal intonations can add to or detract from successful communication. Being aware of and controlling nonverbal cues can enhance effective communication.

Psychological barriers. Once a message passes through physical barriers, it must filter through the receiver’s perceptions. The receiver will attempt to interpret the message consistent with their experience. A person’s field of experience acts as a codebook by which they decode the symbols that compose a message. Since experience is unique to each individual, psychological barriers cause dissonance between the sender’s intention and the receiver’s comprehension. For successful communication, the sender and receiver must share a common understanding of the symbols the receiver used to encode the message.

Specific psychological barriers to communication include semantics, ambiguity, and defensiveness. Semantics is the meaning of words. Different people may attribute a different meanings to words, which can cause misunderstanding. Ambiguity occurs when the meaning of words is unclear to the receiver. The receiver can also be defensive if the message clashes with their beliefs, values, or self-concept.

Feedback

The sender’s intent can differ from the receiver’s understanding (Schermerhorn, Hunt, & Osborn, 2007), especially when the sender and receiver have different languages, cultures, and backgrounds. Feedback is vital for helping to close the gap between the intended message and the understood message. The more diverse the people are, the more critical the feedback becomes.

Feedback is the manner and degree to which a receiver responds to a message (Mehrabian & Weiner, 1967). Feedback is essential for transitioning from one-way transmission to two-way communication that builds lasting relationships. For example, email sending is not communication; it merely sends a message. For communication to occur, the sender must solicit and receive a response. This completes a single communication cycle.

By soliciting and correctly decoding feedback, a sender can understand whether and how the receiver interpreted the message; this allows the sender to adjust the message to match the receiver’s needs. Soliciting and correctly interpreting feedback is key to enhancing the effectiveness of communication. Unfortunately, people often fail to solicit feedback. They may also reject, object to, or reject the feedback they receive. For example, a man might talk at people without being aware of whether the people hear him, let alone understand what he’s saying.

From a systems theory perspective, Bertalanffy (1972) proposed that feedback is essential for generating individual and group growth and performance in human systems. Applied to enhance team effectiveness, team members should be willing to give constructive feedback and welcome feedback from teammates. Similarly, the team should solicit feedback from the environment.

Feedback from the environment can include comparing their performance to other teams and asking instructors or managers for guidance. Accepting and adequately responding to feedback can be difficult, especially if we take feedback personally. However, considering and responding to feedback will help facilitate individual and team development, growth, and self-renewal.

Some valuable tips on feedback include the following:

- Positively offer feedback, even if it is negative. Positive feedback supports and encourages others. For example, “Improving our writing skills can help us get better jobs.” Negative feedback can be destructive to an individual’s development. For example, “You are a terrible writer; you will never get a job.”

- Avoid negative statements that can make the person defensive. Rather than “You are a rude person, and none of us like you,” try, “What do you think we can do to show more respect for one another?”

- Focus feedback on the behavior, not on the individual. For example, rather than saying, “you are a terrible speaker,” try, “Companies are looking to hire people who are good at speaking in public. What can you do to improve your public speaking ability?”

- Open dialogue for questions.

- Make sure you give feedback to the right person; do not gossip to other team members.

- Avoid “toxic” language, name-calling, and labeling.

To enhance individual and team effectiveness, team members should develop practices that reinforce positive behaviors, serve as catalysts for growth, promote self-reflection on an individual and team level, maintain focus, and ensure the process for goal achievement.

![Communication is a process of negotiating to create shared understanding [Image: CoPilot] Communication is a process of negotiating to create shared understanding [Image: CoPilot]](/images/Images/a_man_and_a_woman_creating_shared_meaning_through_communication500.png)

![Your brain can keep growing, adapting, and learning at any age, if you are willing to put in the effort [Image: Copilot]](/images/Images/best-years-for-adult-brain300.png)