When considering the positive results of Team Hachi Project, a collaborative action research project to assess the viability of team learning with remedial students in a lecture-based Japanese university, researchers considered if the Hawthorne Effect was more responsible for improvements than the team learning process they had introduced. This introduced a question about whether the results represented substantive or superficial improvements in student performance and satisfaction (Duncan, 2013). Reviewing assessment, survey, video, and interview data collected during the research cycles illuminated the Hawthorne Effect as a useful tool that teachers can leverage to influence substantial improvements in student and classroom, especially when integrated with scaffolding techniques suggested in Lev Vygotskiǐ’s (1978) theory of cognitive development and situational leadership approaches proposed in Gerald Grow’s (1996) self-directed learning model.

This paper is adapted from:

Duncan, B. (2013). Assessing the viability of team learning with remedial students in a lecture-based Japanese higher education culture. Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest LLC, Fielding Graduate University. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1352039981

This paper was published in the December 2018 issue of Kyiv International University Higher Education Journal

https://kymu.edu.ua/upload/pdf_files/small-group_learning_research.pdf

(C) 2022 by Brent Duncan, PhD. All rights reserved. Contact Dr. Duncan using the Contact Us form at Synthegrate.com.

Summary

To consider the potential impact of the Hawthorne Effect on student learning outcomes in Team Hachi Project, this article will do the following:

- Summarize the research design, process, and results of Team Hachi Project.

- Discuss the Hawthorne Effect's integration with scaffolding and situational leadership practices in a small-group learning environment.

- Conclude that intentionally leveraging the Hawthorne Effect to generate varying levels of attention can be an effective practice for rapidly scaffolding dependent learners toward interdependence and self-direction, improving performance and satisfaction, and fostering motivation to persist.

Team Hachi Project

Thirty student volunteers joined researchers in a simulated four-week course at a private university in Northeast Japan to participate in a collaborative action research project for assessing the viability of team learning in Japanese higher education. Typical for Japanese higher education, small-group learning was a foreign concept for the university and student volunteers (Imafuku, Kurata, Kataoka, & Mayahara, 2010). Despite living in a culture that holds cooperation and collaboration as core values (Nagao, Takashi, & Okuda, 2011), the college experience for the students at the university was like that in other Japanese higher education institutions. In short, while students attend class with other students, they are essentially isolated among others in didactic lecture-test learning environments that do not allow collaboration among students in the classroom (Tsuneyoshi, 2001). The collaborative activities students have with others typically takes place during extracurricular activities and on-the-job training after graduation.

In addition to their lack of experience with small group learning activities in their classrooms, professors had told researchers that the students were too remedial, unskilled, unmotivated, and reserved to learn through mutual development (Duncan, 2018). This laid the challenge for Team Hachi Project, a collaborative action research project to assess the viability of team learning with students in a private community college in northeastern Japan.

Design

Starting with the hypothesis that remedial college students in a rural community college could increase academic performance and satisfaction through small-group learning methods, researchers invited students to act as co-researchers in a collaborative action research project that would simulate a small-group learning environment. Integrating concepts from Team-Based Learning (Michaelsen, 2004) with a work-team model designed for university students, researchers created a process and curriculum that applied Hackman’s dimensions of group effectiveness with action research.

Hackman’s dimensions of group effectiveness

Researchers used the dimensions of group effectiveness defined by Richard J. Hackman (1992) to measure results as follows:

- Goal Attainment. An effective group completes its tasks and accomplishes its goals.

- Satisfaction. Members of the group are satisfied with the process.

- Continuance and persistence. Members of the group are willing to continue working with the group or repeat the process.

Action research

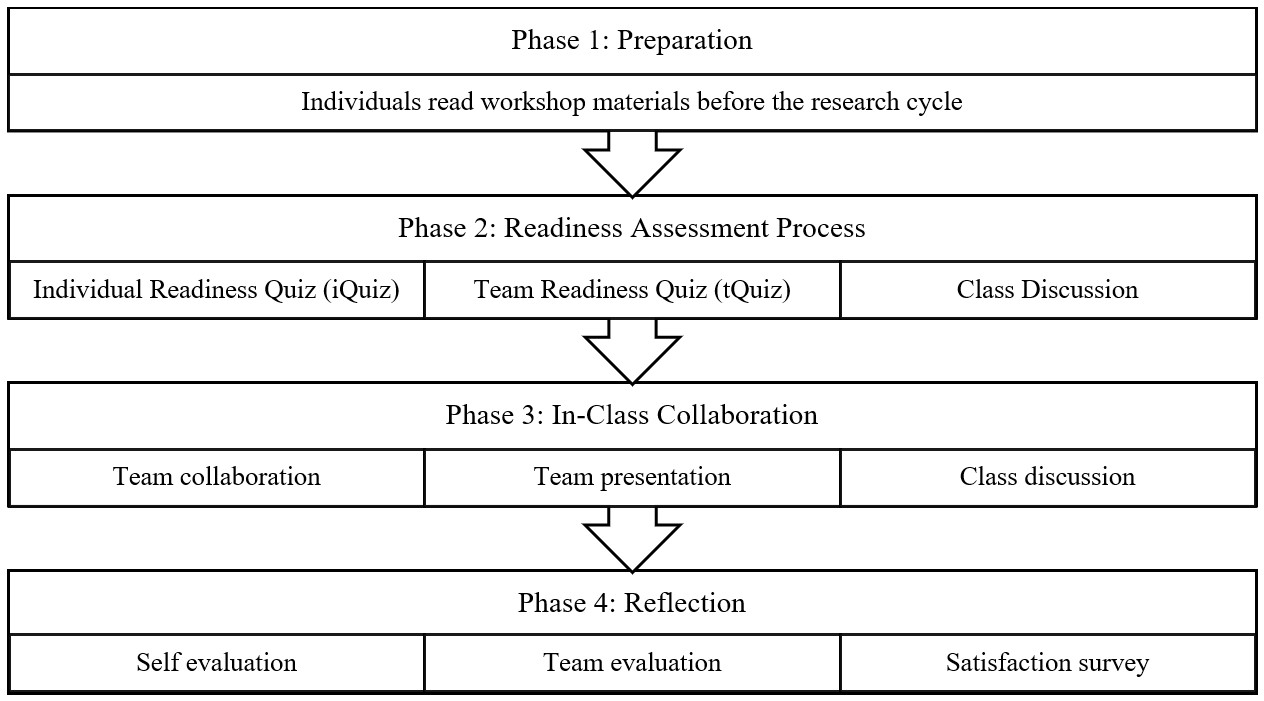

The action research design consisted of four one-week research cycles in a simulated classroom, applying the following phases in each workshop (see Figure 1):

- Preparation. The students prepared for each workshop by reading assigned materials.

- Readiness assessment. Students started each workshop by taking a quiz to assess their level of knowledge and readiness to engage in small-group activities.

- Collaboration. Each student joined a learning team of four other students to discuss the same questions and concepts covered in the readings and readiness assessment to complete the quiz as a group. The comparison between individual and team scores became data to indicate individual learning levels through collaboration. The faculty reviewed the results to identify opportunities for reinforcing and realigning learning in a class discussion. After the discussion, the faculty assigned the teams a project to develop based on the workshop materials, assessments, and discussions. Each team prepared a brief presentation of their project to the class.

- Reflection. At the end of each research cycle, each student completed an evaluation form and satisfaction survey to reflect on what they had learned, record their perceptions of individual and group learning, share their satisfaction with the outcomes, and offer recommendations for improving subsequent cycles.

- Adjust. Researchers evaluated the results of each cycle to identify opportunities for improving the subsequent cycle.

Practice

Each phase in a research cycle provides researchers with opportunities to apply various levels of attention events designed to scaffold individuals and groups to accept increasing levels of interdependence in learning and performance. Based on a technique suggested by Lev Vygotskiǐ (1978), scaffolding means that the teacher acts as a mentor or coach who carefully guides a mentee through the initial stages of learning, gradually removes support so the student can practice toward mastery, then repeats the cycle of engagement to facilitate increasingly higher levels of performance.

Gerald Grow (1996) suggested a practical scaffolding framework in his Self-Directed Learning Model, which applies situational leadership approaches in the classroom for adjusting faculty support based on the readiness and ability of learners to facilitate students toward self-direction in learning.

Applied to a small-group learning environment, the teacher gauges his or her involvement based on the team’s “zone of proximal development” (Vygotskiǐ, p. 86), meaning their readiness to perform the required tasks (Grow, 1996). As the members increase in performance through interdependence, the teacher removes support. In other words, the teacher engages to the degree of the student’s inability. The teacher’s levels of engagement may shift throughout a course to do the following:

- Help individual students acquire and demonstrate the basic knowledge for participating in group activities.

- Provide individuals and groups with the training and tools to work together in teams.

- Administer the coaching necessary to help teams engage in mutual development.

- Withdraw support to observe the students practice, fail, and adjust independently.

- Assert support as necessary to reinforce or realign learning and foster higher performance levels.

Results

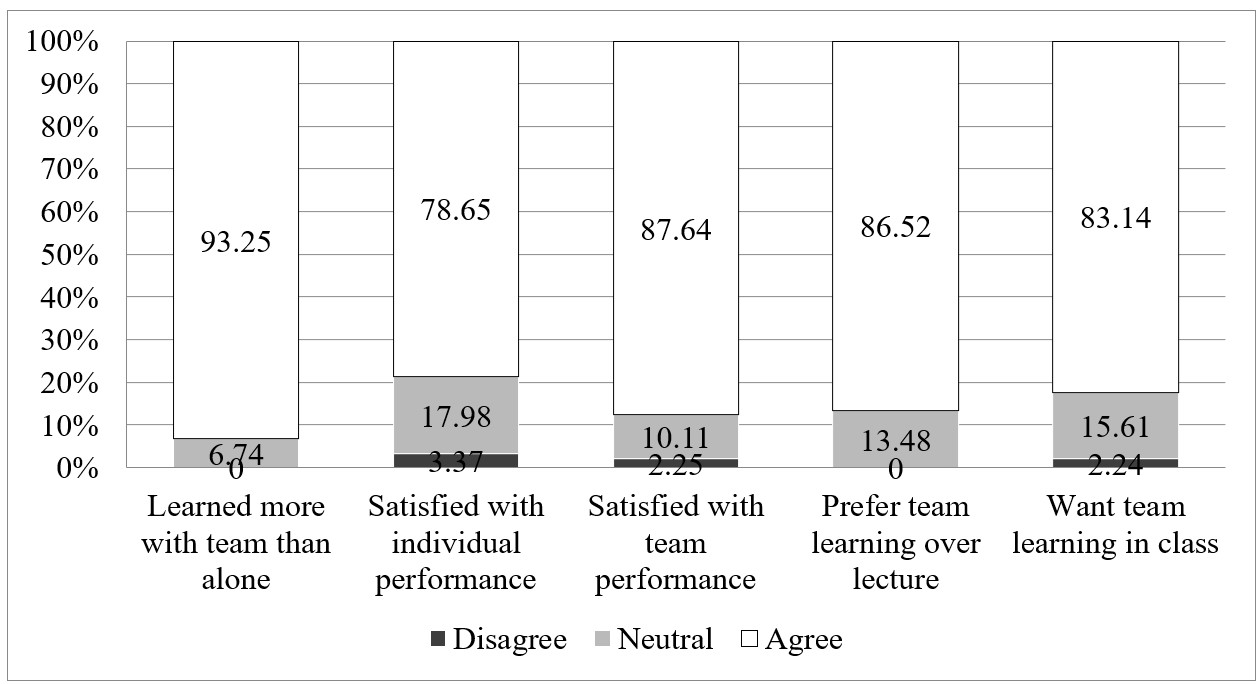

Team Hachi Project researchers gathered qualitative and quantitative data using a combination of classroom assessments, weekly surveys, interviews with students, and video analysis. Consolidating all four cycles of quantitative data from assessments and surveys (see Figure 2):

- Participants reported 93% of the time that they learned more with their teams than alone; a paired t-test supported this finding by showing 98% confidence that students performed better on team tests than when taking the same test alone.

- Participants increased satisfaction with their individual and team performance with each research cycle. Overall, students were satisfied with individual performance 78% of the time and team performance 83% of the time.

- Participants preferred team learning over lectures 86% of the time, with 83% saying they wanted team learning in their regular courses.

- Each measure improved from 7% to 20% in each subsequent cycle.

Integrating with the quantitative data the qualitative information from observations, video analysis, and discussions with students, researchers concluded the following:

- Remedial college students can increase academic performance and satisfaction through small-group learning methods.

- Participants demonstrated the capacity to adapt and perform in a small-group learning environment.

- Students are eager to learn through dialog with one another and in collaboration with their teachers.

- While students appear willing and able to succeed in small-group learning environments, institutional culture and instructor skills remain barriers.

Follow-up interviews indicated that the experience had a transformational effect on some participants, with almost all crediting the experience for helping them develop the confidence and skills necessary to acquire good jobs. Also, all students who started the action research project persisted through the entire four weeks of research cycles and increased engagement with each research cycle (Duncan, 2013).

After the project's conclusion, demand from former participants and other students encouraged the University to repeat the study each semester as a formal series of developmental workshops for students (Duncan, 2013). The second series of workshops had more than one hundred volunteers with comparable results; eight of the students from the original research project volunteered to serve as mentors in the subsequent research cycles.

Through the perspective of Hackman’s (1992) dimensions of group effectiveness (goal attainment), the students achieved the goals of the experiment, were satisfied with the process (satisfaction), and had an increased ability to persist and a strong desire to continue (continuance).

Figure 2. The survey summary shows elevated levels of perceived performance and satisfaction.

Influence of the Hawthorne Effect on performance

Because of direct researcher engagement in administering the research cycles, organizational psychology scholars may question whether performance improvements during Team Hachi Project were skewed more by the Hawthorne Effect than by the team learning methods used for the action research (Jex & Britt, 2014).

The Hawthorne Effect is a concept that emerged from seminal organizational psychology research at the General Electric Hawthorne Works factory in the 1920s. The Hawthorne researchers attempted to assess the influence of environmental variables on worker productivity. Manipulating lighting, temperature, assembly line speed, and other environmental variables, worker productivity tended to increase regardless of the change. Further analysis suggested that the variables were mainly irrelevant. A combination of the attention workers received from the researchers and the social environment created by the project influenced productivity more than environmental manipulations (Adair, 1984; French, 1950).

Although the Hawthorne studies spawned the human relations movement and organizational psychology field (Jex & Britt, 2014; Bateman & Snell, 2007), the Hawthorne Effect is not necessarily a positive aspect of group dynamics because it can disguise research results and temporarily mimic change. This suggests two potential limitations for Team Hachi Project results.

- Performance improvement may occur just by paying attention to people, not by what they are learning.

- Performance increases may be temporary consequences of an attention event. For example, when the boss enters a manufacturing floor, workers may have a sudden burst of productivity as they respond to the alert, “The boss is coming; look busy!” When the boss leaves the floor, the attention event ends. Social homeostasis activates with the boss’ departure, and worker productivity drops below pre-attention event levels.

Applied to Team Hachi Project, critics peeking through the Hawthorne Effect might perceive that researcher observations and engagement influenced behavior more than the small-group learning methods they introduced. However, this perception may obscure the understanding that the Hawthorne Effect can be a valid tool in a collaborative action research project, the classroom, and the workplace. In Team Hachi Project, researcher observation and engagement became tools for scaffolding individual and team development. The instructors intentionally implemented varying levels of attention events to influence student engagement, performance, collaboration, and independence (see Table 1).

Essential differences between Team Hachi Project and the Hawthorne Studies are that Hawthorne researchers (Adair, 1984; Jex & Britt, 2014):

- Attempted to manipulate environmental variables but were oblivious to how their presence influenced subject behaviors.

- Did not attempt to intervene directly in worker practices.

- Did not provide workers with training or tools that could enhance productivity.

In comparison, as collaborative action research, Team Hachi Project did the following:

- Acknowledged and leveraged the researcher as an active mentor who influences participant behavior to improve processes and solve problems.

- Actively engaged the subjects as participants in influencing the development of the study as it progressed.

- Intentionally leveraged attention events to provide substantial instruction, feedback, and tools.

- Facilitated collaborative methods among teachers, students, and groups to influence development at all levels of a dynamic learning system.

Also important, as an action research project that engaged researchers as managers to solve a problem (Ferrance, 2000; Lewin, 1946), Team Hachi Project used student survey data and classroom observations to identify opportunities for improving subsequent cycles. This helped to validate the influence of variables—including researcher involvement—on substantial and durable change.

Table 1. Instructors can leverage attention events as intervention tools to improve students' performance and satisfaction.

|

|

| Instructors plan the next series of attention events while teams collaborate. | The instructor observes team activity to identify intervention opportunities. |

|

|

| The instructor in the foreground explains a challenging concept while the instructor in the background observes another team. | The instructor coaches a team on using a worksheet as a collaborative tool. |

|

|

| The instructor celebrates a student’s correct answer to a challenging question. | The presence of recording equipment is a persistent attention event that motivates performance while capturing data. |

Leveraging the Hawthorne Effect as a developmental tool in the classroom

Considering how researcher or instructor involvement can influence research outcomes by integrating the Hawthorne Effect, scaffolding, and situational leadership illuminates a potentially powerful instructional practice for improving student learning outcomes. In short, as demonstrated in the analysis of the Hawthorne Studies, being unaware of the Hawthorne Effect can diminish potential outcomes and feign change. However, deliberately leveraging attention events to scaffold learners from dependency to mutual dependence and self-reliance can influence positive outcomes and generate lasting change for groups and individuals.

Instructors can apply the Hawthorne Effect as an intervention tool in a collaborative action research classroom using actions like the following:

- Aware. Be aware of how attention events serve as temporary extrinsic motivators.

- Engage. Intentionally engage students in developing and implementing the classroom for individual and mutual development.

- Leverage. Leverage the attention event to generate and foster perpetual feedback loops that encourage students to improve skills and apply new tools for increased performance.

- Reinforce. Promote intrinsic motivation by reinforcing desired behavior through attention events with developmental feedback.

- Scaffold. As the student demonstrates understanding, withdraw from the attention event, monitor performance to determine if behavior changes last, and identify other intervention opportunities.

- Enlist. Once a student demonstrates competence, enlist the student as a mentor for other students.

References

Adair, J. G. (1984, May). The Hawthorne effect: A reconsideration of the methodological artifact. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(2), 334-345. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.69.2.334

Bateman, T. S., & Snell, S. A. (2007). Management: Leading & collaborating in a competitive world (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Duncan, B. (2013). Assessing the viability of team learning with remedial students in a lecture-based Japanese higher education culture. Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest LLC, Fielding Graduate University. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1352039981

Duncan, B. (2018, July 11). Considering Interdependent Learning Models to Align Japanese Higher Education Practices with Japanese Societal Values. Retrieved from Donnach.com: http://donnach.com/index.php/en/explorations/learning/232-considering-interdependent-learning-models-to-align-japanese-higher-education-practices-with-japanese-societal-values

Ferrance, E. (2000). Action research. Brown University, Northeast and Islands Regional Educational Laboratory. Providence: LAB.

French, J. (1950). Field experiments: Changing group productivity. In J. G. Miller, Experiments in social process: A symposium on social psychology (pp. 83-93). Experiments in Social Process: A Symposium on Social Psychology, McGraw-Hill, 1950, p. 82.: McGraw-Hill.

Grow, G. O. (1996). Teaching learners to be self-directed. Adult Education Quarterly, 125-149.

Hackman, R. J. (1992). Group influences on individuals in organizations. In D. M. Dunnette, & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 199-267). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Imafuku, R., Kurata, N., Kataoka, R., & Mayahara, M. (2010, December 3). First-year students' learning experience of problem-based learning tutorials in Japanese higher education. Enhancing learning experiences in higher education international conference. Hong Kong, China: University of Hong Kong.

Jex, S. M., & Britt, T. W. (2014). Organizational psychology: A scientist-practitioner approach. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues, 2(4), 34-46.

McVeigh, B. J. (2002). Japanese higher education as myth. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, Inc.

Michaelsen, L. K. (2004). Getting started with team-based learning. In L. K. Michaelsen, A. B. Knight, & L. D. Fink (Eds.), Team-based learning: A transformative use of small groups in college teaching (pp. 27-50). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, Inc.

Nagao, N., Takashi, I., & Okuda, S. (2011). Motivating learning through a learning team framework [学習意欲を引出すチーム学習の枠組み]. (B. Duncan [Translator], Ed.) Osaka Shin-ai Jokakuin Bulletin, 45, 1-8. Retrieved September 15, 2012, from http://www.osaka-shinai.ac.jp/library/kiyo/45.html

Tsuneyoshi, R. K. (2001). The Japanese Model of schooling: Comparisons with the United States. New York, NY: Routledge.

University of Phoenix. (2004). Learning team handbook. Retrieved October 7, 2008, from Apollolibrary.com: http://www.apollolibrary.com/LTT/toolkit1.aspx?bc=1

Vygotskiǐ, L. S. (1978). The development of higher psychological processes. (M. Cole, S. John-Steiner, & E. Douberm, Eds.) Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.